Early rifles had no mechanical ignition devices or triggers, and they had no priming charges. They had to be ignited by hand and there was still no thought of a hand-held ignition system.

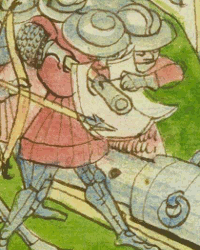

It is assumed that the shooters held glowing pieces of coal or wood chips to the touchhole pan filled with priming herb to ignite the powder charge of the rifle.1) This required the shooter to have one hand half free to ignite the rifle, or a second man was needed to ignite the rifle so that the shooter could put it on with both hands. When the rifle was fired, a considerable amount of the glowing gases escaped through the firing hole, and the shooter had to protect his fingers from this. The shooters did this by using lightning irons. The lightning iron, or lightning hook, is an iron rod bent at a right angle at the front end with an often olive-shaped tip. This tip was heated to red-hot in an ember pan and held in the pan filled with priming herb to ignite the priming herb and the charge of the rifle. For the can to ignite safely, the temperature of the loose iron tip must be well above the ignition temperature of the black powder of 170 °C. In order to prevent the tip from cooling down, the ember pan had to be placed in the immediate vicinity of the can.2) Many preserved tins have distinctly and deeply carved pans at the ignition holes. These lead to the assumption that they were intended to hold the olive-shaped tips of loose irons. In this case, the pan would be filled with priming powder and the glowing olive would be pressed firmly into the pan with the priming powder.3)

In the known written sources in Hamburg we have not yet found any references to loose irons, but we do encounter them in documents of the Teutonic Order, where the treasury of Elbing Castle spent: „… vor 3 entczyndeeysen, 2 bende omme dy busse 3½ scot…” (… for 3 ligthning irons …).4) Further times they appear in the years 1416 and 1425 as "czundehoken" (igniting hook) in entries of the Great Book of Offices of the Teutonic Order.4) In a Frankfurt book of documents they are called "Pengeisen" (receiving iron) in 13915), and for the years 1388 and 1389 the Landrentmeester of Geldern paid 16 gr. for „… 8 haecke tot den donrebussen …” 8 hooks to the blunderbusses.6) Another very interesting mention comes from the account books of the Dutch town of Deventer: "It. Willamme Palmer der stad tymmerman van Zwolle vor een yseren kystiken daer men vuer inne besluet die bussen hake mede te heyten alse men in den velde mit den bussen meynt te schieten 1 gl. 26 gr." According to this, the municipal carpenter from Zwolle, Willamme Palmer, received 1 guilder 26 gr. for an iron-lined box in which embers are kept in which the "bussen haken" (gun hooks) are heated with which the rifles are fired in the field.7)

In the known written sources in Hamburg we have not yet found any references to loose irons, but we do encounter them in documents of the Teutonic Order, where the treasury of Elbing Castle spent: „… vor 3 entczyndeeysen, 2 bende omme dy busse 3½ scot…” (… for 3 ligthning irons …).4) Further times they appear in the years 1416 and 1425 as "czundehoken" (igniting hook) in entries of the Great Book of Offices of the Teutonic Order.4) In a Frankfurt book of documents they are called "Pengeisen" (receiving iron) in 13915), and for the years 1388 and 1389 the Landrentmeester of Geldern paid 16 gr. for „… 8 haecke tot den donrebussen …” 8 hooks to the blunderbusses.6) Another very interesting mention comes from the account books of the Dutch town of Deventer: "It. Willamme Palmer der stad tymmerman van Zwolle vor een yseren kystiken daer men vuer inne besluet die bussen hake mede te heyten alse men in den velde mit den bussen meynt te schieten 1 gl. 26 gr." According to this, the municipal carpenter from Zwolle, Willamme Palmer, received 1 guilder 26 gr. for an iron-lined box in which embers are kept in which the "bussen haken" (gun hooks) are heated with which the rifles are fired in the field.7)

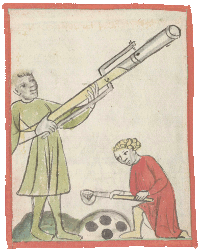

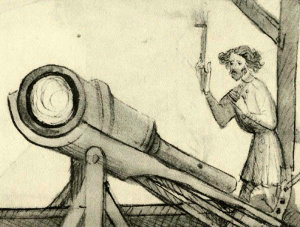

LIighting irons were in use until the middle of the 15th century and were gradually replaced by fuse ignition as powder and fuse recipes became more refined, with a piece of smouldering slow match held to the powder pan for ignition. Here, too, there was a risk of burns for the shooters due to the combustion gases escaping from the fuse hole. To create a safe distance between the match and the shooter's hand, the shooters used match sticks. A piece of smouldering fuse was clamped into the forked end of a wooden stick. Early illustrations already show simple, lever-shaped matchlocks in which the match holder had to be manually lowered onto the powder pan and lifted off again, as illustrated in an illustration from Konrad Kyeser's Bellifortis of 1411.8) This mechanism made it possible to place the rifle with both hands and trigger the shot at the same time. However, these solutions did not become generally accepted. It was not until later, in the second half of the 15th century, that the first mechanical trigger devices were developed in the form of matchlocks with spring mechanisms and snap-locks.2) For guns, firing by means of a matchlock was retained until the introduction of breech-loading systems in the 19th century.

LIighting irons were in use until the middle of the 15th century and were gradually replaced by fuse ignition as powder and fuse recipes became more refined, with a piece of smouldering slow match held to the powder pan for ignition. Here, too, there was a risk of burns for the shooters due to the combustion gases escaping from the fuse hole. To create a safe distance between the match and the shooter's hand, the shooters used match sticks. A piece of smouldering fuse was clamped into the forked end of a wooden stick. Early illustrations already show simple, lever-shaped matchlocks in which the match holder had to be manually lowered onto the powder pan and lifted off again, as illustrated in an illustration from Konrad Kyeser's Bellifortis of 1411.8) This mechanism made it possible to place the rifle with both hands and trigger the shot at the same time. However, these solutions did not become generally accepted. It was not until later, in the second half of the 15th century, that the first mechanical trigger devices were developed in the form of matchlocks with spring mechanisms and snap-locks.2) For guns, firing by means of a matchlock was retained until the introduction of breech-loading systems in the 19th century.

In all cases of ignition by means of ligthing irons or slow matches, an open source of fire was necessary for the safe supply of the means of ignition. Various containers were used for this purpose, such as lanterns with burning candles or special embers containers, which kept the embers safe even in the field or in bad weather. There are several references to ember containers in the Tressler books of Marienburg Castle of the Teutonic Order. The invoice entry in connection with the expenses of the arsenals master from the year 1401 for: "2½ m. vor 4 kolpfhannen und 5 scot vor 1 pulversyp …" (2½ m. for 4 coal pans and 5 scots for 1 powder sieve…). (2½ m. for 4 coal pans and 5 scot for 1 powder sieve)9), points to the procurement of ember pans for rifles or guns. Another invoice entry dated 9 August 1409, also from the Marienburg Tresslerbuch of the years 1399–1409 mentions expenditure by the chamberlain of: '4 scot before 4 polfermesechen of bleche made and before 4 roren, do der bochsenschocze fuwer mag inne tragen' 4 scot for 4 powder measures of metal sheets and 4 tubes to carry fire in them. A similar entry is handed down from the inventory of the armoury of Bologna from 1397: "… 14 ferros ad trandum ignem".10) These "roren" are either purely ember containers or possibly also luntenbergs for storing smouldering slow matches.

In all cases of ignition by means of ligthing irons or slow matches, an open source of fire was necessary for the safe supply of the means of ignition. Various containers were used for this purpose, such as lanterns with burning candles or special embers containers, which kept the embers safe even in the field or in bad weather. There are several references to ember containers in the Tressler books of Marienburg Castle of the Teutonic Order. The invoice entry in connection with the expenses of the arsenals master from the year 1401 for: "2½ m. vor 4 kolpfhannen und 5 scot vor 1 pulversyp …" (2½ m. for 4 coal pans and 5 scots for 1 powder sieve…). (2½ m. for 4 coal pans and 5 scot for 1 powder sieve)9), points to the procurement of ember pans for rifles or guns. Another invoice entry dated 9 August 1409, also from the Marienburg Tresslerbuch of the years 1399–1409 mentions expenditure by the chamberlain of: '4 scot before 4 polfermesechen of bleche made and before 4 roren, do der bochsenschocze fuwer mag inne tragen' 4 scot for 4 powder measures of metal sheets and 4 tubes to carry fire in them. A similar entry is handed down from the inventory of the armoury of Bologna from 1397: "… 14 ferros ad trandum ignem".10) These "roren" are either purely ember containers or possibly also luntenbergs for storing smouldering slow matches.

In addition, gunsmith and fireworks books provide numerous suggestions for the production and storage of embers and fire. A fine example of this is provided by the author of the Fireworks Book of 1420, whose name is not known and which is available to the Staates Library of Berlin as a print from 1529: "How one should make a fire which one stirs up or carries [with him] without great worry for half a day or a whole day or night, and that he can light a sulphur candle on the same fire when he comes to the place where he needs fire. Take large rushes of moss, such as are found by the ponds and in the mosses, and boil the rushes in good wine in which saltpetre has been boiled. And when they are boiled, take them out, and dry the rushes in the sun, and strip them of the green outermost skin, and lift them upon a burning coal, that it may kindle the fire. You carry [them] for a span of a mile, and if you want a fire, put a sulphur candle on it, and you will have fire."11)

Historic Sources

Three lighting irons and a match stick from the 14th to 17th century, former private collection Michael Trömner †, Abensberg, Germany.

PhFoto: Michael Trömner)

Lighting iron of unknown date, possibly 18th or 19th century, Reichstadtmuseum Rothenburg o. d. Tauber, Germany.

Ignition of a stone box by means of hot ligting iron. Konrad Kyeser: Bellifortis. ca. 1405, Sate and Universitty Library of Göttingen 2° Cod. Ms. philos. 63 Cim.

References

- Hassenstein (1941): pp. 116-117

- Schmidtchen (1977 b): pp. 60-62

- Own observation of cans and loose irons from the private collection of Michael Trömner and other museum collections.

- Rathgen (1928): p. 439

- Rathgen (1928): p. 25

- Jacobs (1910): p. 115

- Doorninck (1888): p. 94 - Vielen Dank an Bertus Brokamp

- Hartlieb, Kyeser (1411): Fol. 38v

- Engel (1897): p. 232

- Schmidtchen, Volker (1977 a): p. 72

- Feuerwerkbuch, Abschnitt 84, in Sammelhandschrift (1529), Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Ms. germ. fol. 94 (nach Hassenstein (1941))

Text and photo: Andreas Franzkowiak